Running rum back

To consider more critically its contexts of colonialism, diaspora, and tropical fetishism

The last time I was here I wrote about Gasparilla, a gigantic marketing platform for Captain Morgan, and ever since then I’ve been thinking a bit more critically about rum, with particular attention to how Florida’s cocktail culture—which is very rum-soaked in general—acts a visible gesture toward colonial and diasporic histories of the state.

A proverbial potlikker of the spirit world—seventeenth-century planters weren’t interested in the byproducts of sugar production—rum makes up just about every cocktail I can think of that’s associated with Florida in the cultural imagination:

the bushwacker, made famous at the Sandshaker in Pensacola (the recipe came from the British Virgin Islands);

the mojito, an evolution of the sixteenth-century el Draque popularized in the 1860s by Havana-based Bacardi;

the rum runner, tossed together in the 1950s at a bar looking to clear shelf space in the Florida Keys;

the piña colada, born in San Juan and the national drink of Puerto Rico;

and the Hemingway daiquiri, so named because Ernest wanted extra rum, no sugar in his cocktail at a bar in Cuba.

As is hopefully evident by the list above, a lot of the cocktails associated with Florida are indicative of a broader umbrella under which it falls along with the rest of the Caribbean region: histories of competing colonial powers; diaspora; and a fetishization of the tropics as a place of respite, refuge, and escape.

I enjoy a zesty mojito poolside; I’ve ordered many a painkiller to slurp alongside my oysters. I drank my fair share of Hemingway daiquiris while homesick in Mississippi, and I was overjoyed when I saw a bushwacker (a blended, frozen mix of dark rum, amaretto, coffee liqueur, Coco Lopez, creme de cacao, and milk) on the menu at a Mexican restaurant in Birmingham, of all places.

Yet I can’t help but think about how most of these cocktails don’t come from Florida at all, which says a lot about the state’s geopolitical position as a borderland between the US and the Caribbean.

You can’t talk about the history of rum—and its ties to Florida—without talking about the ocean. Rum has long been tied to the movement of bodies and goods across water.

In Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History, Frederick H. Smith intervenes in the study of Caribbean commodities to assert the impact of the product on the societies that produced it—centering what rum meant to enslaved Africans, to servants, and to peasants who made and drank it as opposed to focusing solely on how rum transformed the macroeconomy. (For that, you can read this.)

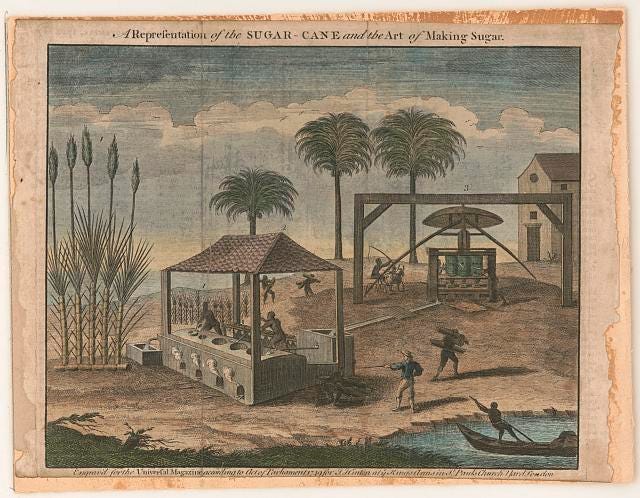

Early sources, Smith says, allude to several rum prototypes: guarapo, a fermented sugarcane juice made and consumed predominantly by enslaved Africans in the Spanish colonies attempting to preserve traditions from West Africa, and brusle ventre (stomach burner) made in the French territories. A number of other fermented molasses drinks were produced throughout the Caribbean, but by 1650 what would collectively become known as “rum” had formalized in the presence of still houses on sugar plantations, first documented in Barbados by an English colonist who thought the drink was so strong he called it “Kill-Devil.” Stills would eventually become essential to the sugar plantation complex, as rum largely paid for the operational expenses of the plantations. Sugar, on the other hand, translated into direct profits.

Bringing the comparison to potlikker back to the fore, it’s worth emphasizing that the third-highest selling spirit in the world, globally worth nearly $18 billion in 2022, originated from the fermented waste—molasses—of sugar production, discarded by disinterested European planters and repurposed by enslaved African laborers.

Sit with that one for a little while.

Despite its reputation as a gateway to the Caribbean, there’s no telling how much rum came in and out of Florida before the 1920s. Most historical records point to exports to British colonies, and most histories of rum in Florida seem to start with rum-running about one hundred years after Florida was acquired from Spain as a US territory. What is known is that some enslaved laborers were trafficked into Florida from the Caribbean because it was faster and cheaper. It’s possible that they brought with them their knowledge of and palate for rum. (After it became recognized as a viable commodity, rum was later rationed to laborers in the Caribbean, some receiving on average around 9 gallons per year.)

What’s also known is that Florida was targeted by pirates (like Henry Jennings) and merchants alike; rum was used for bartering in the Atlantic maritime world and likely passed through Florida’s ports too, particularly if it was rum from Cuba or Jamaica.

Fast forward a little bit: Spain gives Florida up to the US and it’s eventually admitted to the union. No one really cares about it because it’s swampy and gross until two industrial magnates (both named Henry) build railroads on opposite coasts. Snowbird culture is born, and the rich and famous start traveling down to the steamy wasteland to spend their winters in fancy hotels by the beach (remember what I said about respite, refuge, and escape). In 1916, Florida elects a teetotaling governor and Prohibition kicks off three years before the Volstead Act bans the manufacture and sale of liquor for the whole country.

Okay, we’ve arrived at rum-running. Press Play.

Rum-running (which generally refers to any alcohol transported across the water, including gin and whiskey) was a massive enterprise. In Florida, this meant ferrying rum from Cuba and the Bahamas to Miami and the Keys. It also meant war with the Coast Guard. Shots were fired, boats were sunk. It happened all over the place (all the way up to Canada, and Texas too) but it’s become woven into the cultural fabric of Florida, particularly in the Keys. The bartender in Islamorada could have named his rum-banana-grenadine concoction anything, but he went with rum runner and now you can order some version of it in bars all over the world.

It’s sweet and fruity and hits the spot on a hot day—particularly if served alongside a basket of conch fritters or a freshly steamed snow crab. But it’s worth careful consideration, too. Rum-running was just one stage of rum’s longue durée, which shouldn’t be watered down by Jack Sparrow caricatures and pastoral images of palm trees. Rum came from enslaved labor; it came from imperialism; it came from the sea. These things bind Florida and the Caribbean together, and there would be no rum without them.

I guess my point is this: If we think about rum the way we think about potlikker, we can see it as a product of agency and ingenuity. If we think about the rum runner cocktail as an allusion not just to twentieth-century smuggling but to a longer relationship to imperial power, we can better understand the interconnectedness of Florida and the Caribbean.

Field Notes: I drove around the Orlando Milk District last month and spotted the T. G. Lee headquarters. I didn’t think I’d love cow print so much, but it was everywhere from murals to newsstands. Super cute. T.G. Lee was a good ole farm boy from Orlando, fyi.

Tasting Notes: One of my favorite Florida gals on this planet, Devon, is co-owner of Liba Spirits, a nomadic distilling company that takes her around the world where she makes super cool things like rum and gin. Liba’s botanical rum, Lafcadio (named for Lafcadio Hearn), is super herbaceous and delish. Follow her on Instagram and scoop some here!

End Notes: I love this piece in Saveur—though I could live without all the pirate puns, tbh—about the opportunity rum-running presented to women, who “took advantage of the damage that Prohibition had done to the alcohol market in the 1920s and found a foothold in an arena that had long excluded them.” I’m obsessed with the story of Marie Waite. Known as Spanish Marie, she took over her husband’s rum-running empire after he was mysteriously found dead, and she installed radios in her ships so that runners could communicate with each other. There’s a brewery in the Keys named after her, and a rum called Bad Bitch Spanish Marie.