The last time I was here—which, hides behind hands, was a long time ago—I wrote about Castro, Cuba, the mafia, and milkshakes. It’s been a while since I’ve written anything else: I started a PhD program at the University of Florida last fall and that sucked up whatever free time I had left in my already hectic schedule. The first semester was a bit of a struggle (read: I had a hard time) as I tried to balance two rigorous seminars, the coursework that came with them, and a full-time job, which didn’t leave me much room for anything other than mainlining espresso and taking the occasional shower.

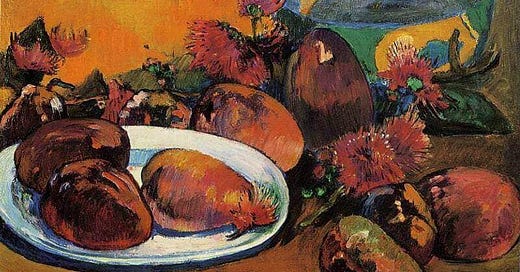

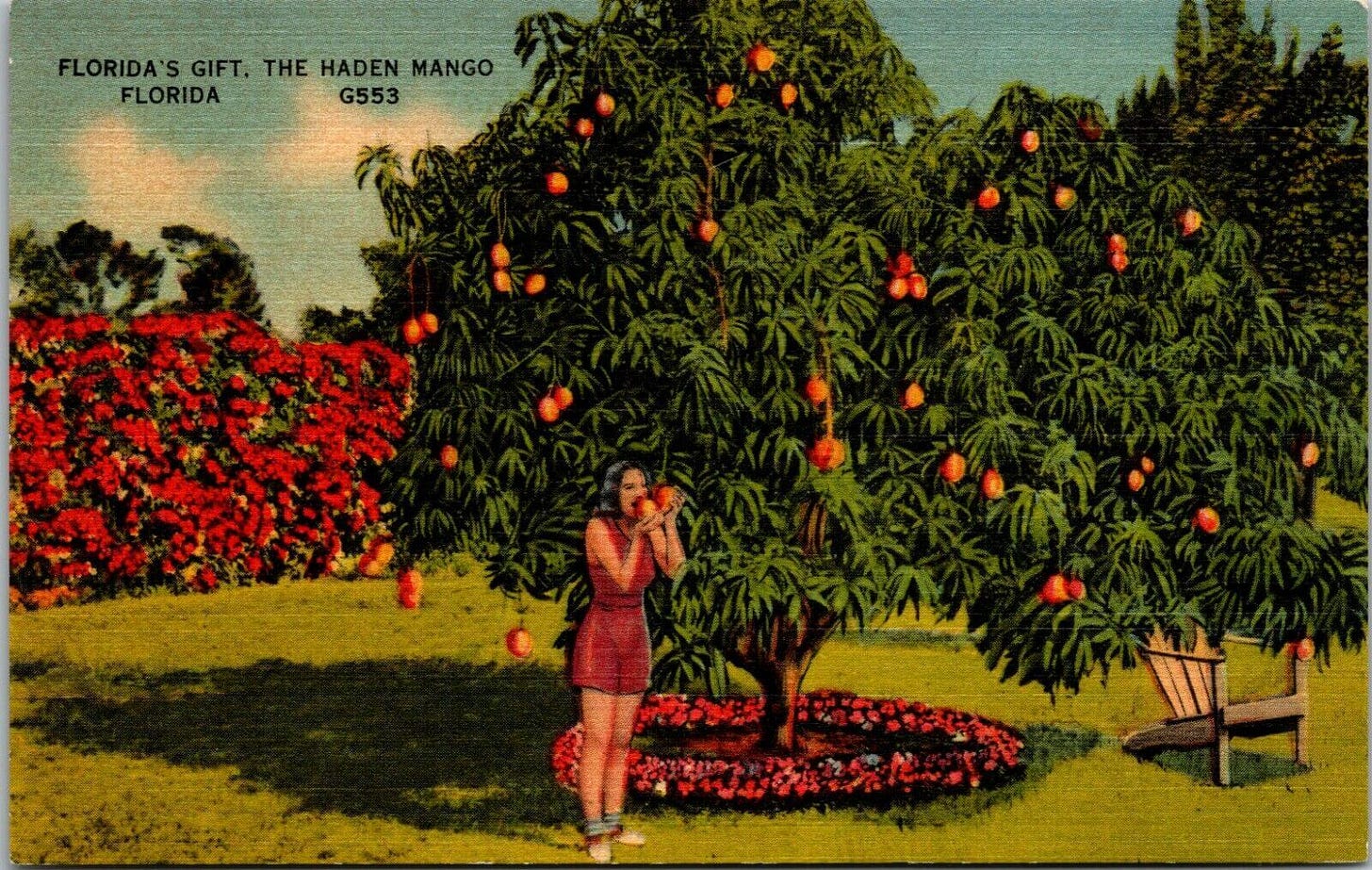

I seem to have figured out the balance, though, because I just wrapped up my first year of coursework and can now return once again to the things that I enjoy, like reading for fun (I just got through Annabelle Tometich’s The Mango Tree: A Memoir of Florida, Fruit, and Felony), touring art exhibits (there was a stellar surrealist capsule up in Gainesville recently), making fancy desserts just because (Eric Kim’s olive oil ice cream is a never-failing favorite), and writing about whatever I want (I’m dabbling in poetry I guess?).

Because it’s been so long, when I sat down to pick up this newsletter again I wasn’t sure where to start. Scientists recently found signs of citrus greening in Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’s still-producing orange groves, and that deserves to be written about. I recently learned of a Florida food writer who was drinking buddies with Ernest Hemingway, and I want to know more about him. I’d still like to wax philosophic on Jack Kerouac’s favorite bar in my hometown of St. Pete, and there’s also this Jacksonville cookbook that I just got my hands on…

I’m going to focus instead on The Mango Tree, Annabelle Tometich’s gorgeous memoir, because I think everyone should read it whether they’re a Floridian or not. I’ll lay out my case—and then maybe the next time I sit down to write, I can tackle one of the topics above.

Tometich was born in Fort Myers, known to most people probably because of Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Hurricane Ian. Her mother immigrated to the US from Manila as part of the nursing pipeline established by nineteenth-century American imperialism in the Philippines; her father, whose family left a war-torn Yugoslavia, was not around for most of her childhood.

The memoir picks up when Tometich is an adult, attending a hearing for her mother who was arrested for shooting a BB gun at a man stealing mangoes from her front yard. A food writer for the News-Press—who revealed herself, in 2020, as the mysterious restaurant critic behind the paper’s 40-year Jean Le Boeuf pseudonym—Tometich and her family became fodder for news outlets across the country clickbaiting with the “typical Florida” story of absurdity and violence.

For a while, Tometich said, when you Googled “mango shooter” the search results showed first her mother’s mug shot and then an Absolut Vodka cocktail recipe.

Tometich uses the shooting to frame the book, but the majority of the memoir takes place during her childhood. With a clear gaze and unflinching honesty, she describes her struggle for a sense of identity against a backdrop of sweltering Florida summers and a tumultuous relationship with her mother, who herself is torn between her life in Florida, her family in the Philippines, and a slow spiral into manic depression.

Memoirs can be tricky: Usually there has to be some message in them that’s going to resonate with readers (unless you’re famous, and then I guess that doesn’t matter). I thought for a long time about what the message of The Mango Tree was. I can list a few, but there’s one that stands out the most.

The headline of the New York Times review of The Mango Tree reads: Mango. Gun. Handcuffs. Could a Story Get Any More Floridian? When I read this a few weeks ago, I wanted to scream. Sure, the headline is an allusion to the memoir’s main hook; fine. But it’s not truly what the memoir is about, nor is it what makes the story Floridian. To a non-Floridian whose concepts of the state are still plagued by images of Florida Man and tropical fetishism, I guess it makes sense. But I’m going to be honest, it’s boring and by this point pretty dated (spread the word).

I lead a monthly book club at Lauren Groff’s new bookstore in Gainesville, The Lynx, and The Mango Tree was our first read. With Tometich in attendance on Zoom, I asked the folks in the room: “What made this a Florida memoir to you? Mangoes, guns, and handcuffs, or something else?”

People talked about the weather, the landmarks, the sense of place. Tometich uses storms, for example—hurricanes in particular—as a metaphor for tempestuous interpersonal relationships, particularly those that involve her mother. “We are the eye of the storm, us and Mom. We are the calm. Life and death swirl around us” (134). She talks about nobodiness—”Nobody is from Fort Myers”—and the feeling that everyone she encounters is a somebody she doesn’t quite measure up to. She describes living in a state of perpetual sweat; of growing up with the cautionary tale of Adam Walsh. (It should be noted that all Florida kids grow up with some cautionary tale about violence against children; mine was Carlie Brucia, my sister’s was Parkland.)

And then there’s the element of migration, which we didn’t talk about in book club but that I think warrants reflection. The flow of people in and out of the region—from the Philippines or Yugoslavia, from the Caribbean, from California or Texas or New York—has been a hallmark of Florida since European contact. I’m not as versed on Indigenous histories of the state as I’d like to be, but I suspect there was a fair amount of movement then, as well. This heavy traffic (both literal and metaphorical if you’ve ever tried to drive around downtown Tampa or Miami during rush hour) has indelibly left its mark on what we call “Florida culture,” a sticky term with no concrete definition, and I think it makes it hard for anyone here to feel like a somebody. What do you identify with in a place that’s so diverse and hard to define?

(When I was in DC last, at a food history event at the Smithsonian, I told someone I was from Florida and she immediately responded with a scrunched face and thinly veiled disgust. “I just can’t talk about that place,” she said. And just like that, she was a somebody and I was the nobody.)

What makes Tometich’s memoir sing, I think, is the way it vacillates between a prominent Florida duality: Florida as it is perceived (or constructed to be perceived by narratives imposed on it) and Florida as it is experienced. Structuring the memoir the way she does, framed as a “typical Florida” story that actually goes beyond the headlines, is something more and more Florida writers are trying to do. Because there is, spoiler alert, more to a Florida story than mangoes, guns, and handcuffs.

There are real people, too.

I’m going to close by very briefly quoting a different author, because I think it relates to this fascination with the “typical Florida” narrative. Kent Wascom just published a neo-Western, southern gothic, techno-futurist novel, The Great State of West Florida. At a talk at The Lynx this week, he told us he thinks of Florida, a place that sees more interstate migration than any other, as a mirror for the rest of the nation.

Hold the mirror up. If you don’t like what you see, turn that gaze inward and consider why.

Field notes: I’ve talked a lot about The Lynx, and that’s because I’ve been spending a lot of time there lately. I lead the Florida Literature Book Club, and I invite you to read along, if you feel moved, even if you can’t be here physically. Next month we’re reading Say Hello to My Little Friend by Jennine Capó Crucet, a novel that reads like Scarface meets Moby Dick (yes, I took that from the blurb). I’d love to hear what you think.

Tasting notes: Here’s the recipe for the Mango Shooter cocktail, which Tometich provided as part of a book club discussion kit:

2 ounces clear liquor (vodka, gin, or tequila—or water, for an NA version)

1.5 ounces mango puree

1 ounce fresh lime juice

(Optional) 1 ounce simple syrup

1-2 twists cracked black pepper

Ice

Sparkling water

Combine liquor, mango puree, lime juice, (simple syrup,) and black pepper in a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake vigorously until the shaker is cold to the touch and frosty (15-20 seconds). Strain into a glass filled with fresh ice, top with sparkling water, and add peppercorns and lime for garnish.

End notes: Tometich has written a bit about what it meant to her to publish under a French man’s name, how it lent credit to her work and afforded her opportunity as a woman of color. “I’m a half-Filipina, half-Yugoslavian/English/Canadian woman, born one year after Le Boeuf was created in the same place he was created: a city named for a Confederate colonel. … I’d always been seen as Brown, as mixed, as never quite enough. But as Le Boeuf I could wield the ultimate power: Whiteness.” Listen to her talk about her Washington Post op-ed here.

Adored this window into your brain and appreciate this analysis. Excited for the next!