The last time I was here, I wrote about rum running, and I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways in which cultural production in and about Florida is shaped by caricature. There’s pirate lore based on archaeological excavations like Mel Fisher’s and booned by tales of modern piracy (read: rum running). There’s Disney, which lords over Orlando à la the Vatican and cloaks corporate greed in social justice wearing Mickey Mouse ears. And then there’s Florida Man.

Choose your fighter.

The Florida Man meme is borne of two things: broad public records laws and internalized class bias. Over time, headlines about men—usually poor, usually white—committing some social faux pas or another, like having sex in a Taco Bell bathroom or carrying an alligator into a 7-Eleven, crystallized into the mascot for white trash. Like a calling card, the Florida Man (and Florida Woman) meme came to symbolize any behavior deemed unfit by “civilized” society, a marker of an “us versus them” mentality that positions anyone who doesn’t fit the bill as respectable—could be poor, could be uneducated, could be disabled, could be just having a really hard time—as an outside Other.

Someone called 911 after their kitten was denied entry into a strip club? Florida Man. Someone tried to get an alligator drunk? Must be Florida Man. Then there are the really dark ones: Someone got high and ate another man’s face? Someone tried to perform a castration at home? Someone had sex with a dog? Got—to—be Florida Man. (They were men who lived in Florida, for the record.)

As Nancy Isenberg explains, “white trash” as a concept evolved from the U.S. colonial period, when Britain considered the territory as a place to send the prisoners and idle poor. (“He’ll be shipped off to the Americas!”) It’s no coincidence that, even as an independent nation, the U.S. has held on to that same paradigm. As American colonists replicated the imperial practices of their forefathers and began colonizing other territories for the sake of expansion and the wealth that could be extracted from it, the same attitude would arise with regard to new places—like Appalachia. And like Florida.

Funny enough, Ernest Matthew Mickler starts off the introduction to White Trash Cooking (Ten Speed Press, 1986), his much-celebrated, spiral-bound cookbook, by saying, “Never in my whole put-together life could I write down on paper a hard, fast definition of White Trash.”

So maybe I went about this the wrong way.

He goes on to say: “You all know, and we won’t let anyone forget it, that the South is legend on top of legend on top of legend.” (Maybe I didn’t go about this the wrong way.) “Just read the stories of Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Truman Capote, and Tennessee Williams. Listen to the songs and stories of Jimmy Rodgers, Mother Maybelle Carter, Hank Williams, Loretta Lynn, Elvis Presley, and Dolly Parton. They all tell us, in their own White Trash ways, that our good times are the best, our bad times are the worst, our tragedies the most extraordinary, our characters the strongest and weakest, and our humblest meals the most delicious.”

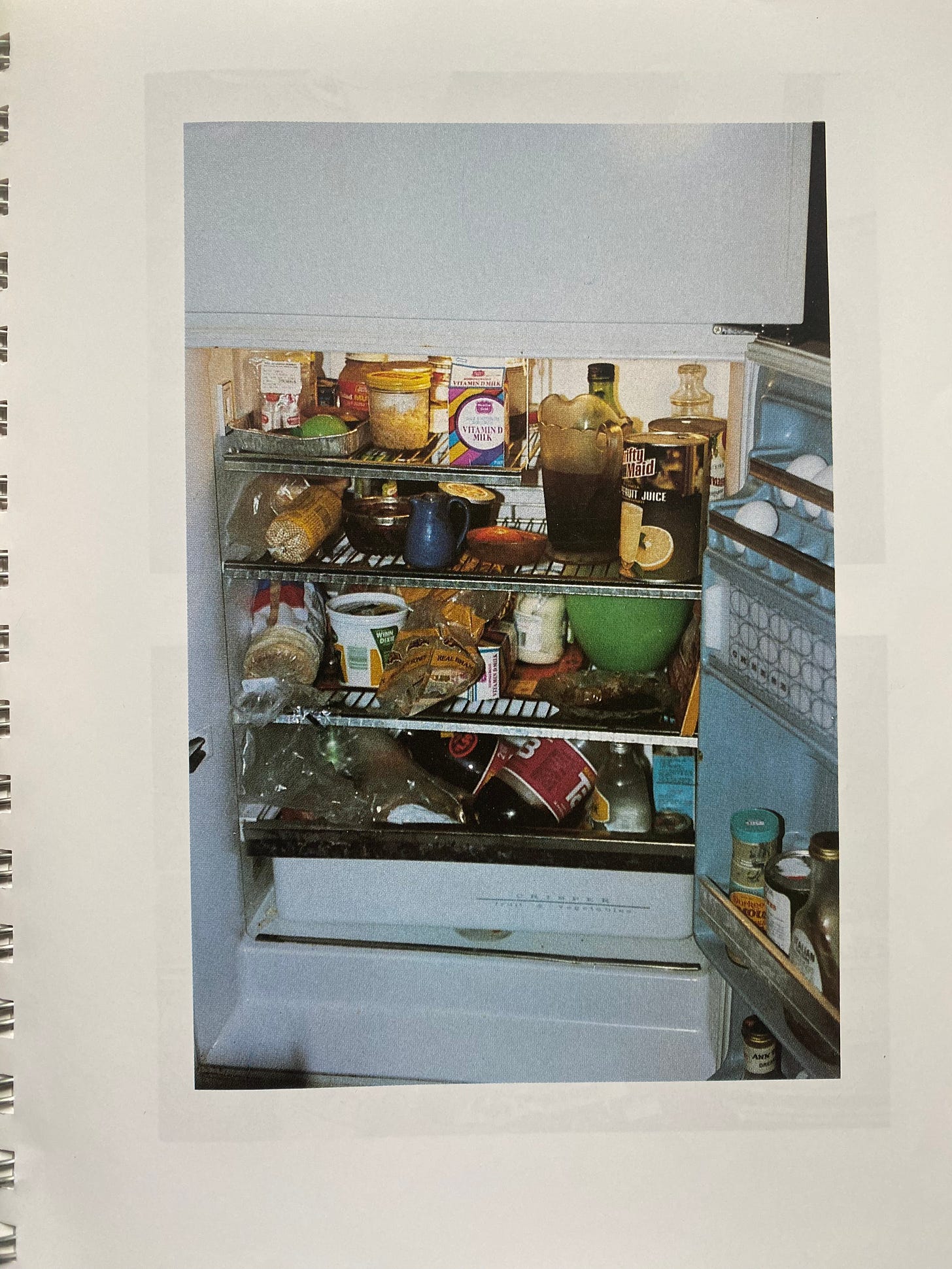

Mickler was born in Palm Valley, just south of Jacksonville Beach, a place that was made up of “shotgun shacks, fish camps, and moonshine stills set back in the sticks.” Equal parts folklore, visual archive, cookbook, and love letter, White Trash Cooking has very quickly become one of my most prized possessions. I recognize the voice on the pages; I know what the recipes taste like. Because Mickler, who was a man like none other, writes about North Florida in a way that is likely recognizable to anyone with roots there. (And I’ll preface this by saying that northwest and northeast Florida are very different. Even in northwest Florida, home of the Redneck Riviera, there’s nuance: Port St. Joe and Pensacola are two markedly distinct places.)

I thumbed through the book with my mom—who grew up in Wewahitchka, where she walked to school barefoot and people caught crabs in the bay for dinner—to get her comments. She wrinkled her nose at the stewed cabbage. Laughed gleefully at the bottles of Tab and references to Crisco. “We have one of those!” she said, pointing to a picture of an iron heating on a stove, “but we use it as a doorstop now.”

Together, the recipes, the text (“snapbean prose”), and the images all point toward a kind of subsistence cooking, where you don’t have much to make but you can still make it good. Jail-house chili. Day-old fried fish. Chicken feet and rice. Liver-hater’s chicken livers. Five-can casserole (canned chicken counts as one can). Broiled squirrel (“Squirrel is one of the finest and tenderest of all wild meats.”). Soda cracker pie.

Clara Jane’s fried apples (apples fried in butter and that’s it) make a perfect topping for pork chops. Ritz pie is made with precisely 23 Ritz crackers—”One more cracker and you’d ruin the whole thing!”—sugar, vanilla, eggs whites, and pecans. Scalloped taters calls for one can of milk and enough water to make it two cups.

Our humblest meals the most delicious.

Chris Offut reminds us of once-considered trash foods that have now become culturally accepted: “crawfish because Cajun people ate it, and catfish because it was favored by African Americans and poor Southern whites. As these cuisines gained popularity,” he writes in the Oxford American, “the food itself became culturally upgraded. Crawfish and catfish stopped being ‘trash food’ when the people eating it in restaurants were the same ones who felt superior to the lower classes. Elite white diners had to redefine the food to justify eating it. Otherwise they were voluntarily lowering their own social status—something nobody wants to do.”

I’m reminded of Mickler’s recipe for five-can casserole. When The New York Times publishes a listicle that celebrates canned chicken, will it suddenly get an end cap in grocery stores? When chicken livers make their way onto tasting menus in Chicago or D.C. or San Francisco, will people no longer turn their noses up?

And what happens to Florida Man during all of this?

The discourse around trash food has largely been driven by Appalachians tired of the hillbilly stereotype. “People from the hills of Appalachia have always had to fight to prove they were smart, diligent, and trustworthy,” Offut writes. “It’s the same for people who grew up in the Mississippi Delta, the barrios of Los Angeles and Texas, or the black neighborhoods in New York, Chicago, and Memphis... I’ve been called hillbilly, stumpjumper, cracker, weedsucker, redneck, and white trash—mean-spirited terms designed to hurt me and make me feel bad about myself.”

Beverly Hillbillies, I’d like to introduce you to Florida Man.

If Floridians stake a claim in their food (or any part of their culture that can’t be distilled to corporate consumption) and find reasons to celebrate it—trash and all—will we see a reckoning with Florida Man? Since White Trash Cooking was published in 1986—and it almost wasn’t, when a Boston publisher said that the title would offend “three-quarters of the United States”—there’s been a slow recalibration of how we think about the foods of poor people. And yet, during that time, we also saw the birth of a new stereotype. Only Florida Man would eat alligator. And as Appalachian culture undergoes a renaissance, Florida remains defined by caricatures.

“While some states are known for their food or architecture, Florida is known for the ‘Florida man.’”

Field notes: We’ve entered my favorite Florida season: the last gasps of spring. Every few days we get a whip of cooler air in the morning, but by afternoon the summer storms start rolling in and the skies turn yellow with the promise of heat to come. The air smells wet—like grass, like thunder, like slate. It’s the kind of smell that can remind you of how small you are, but in a good way, like a hug. It’ll be gone by next week.

Tasting notes: My friend Nina has a peach tree in her front yard and the peaches were ripe ripe ripe, so the other day we stood barefoot in the grass and plucked a Pyrex-full and zipped them in the blender with light rum and lime juice. Wednesday daiquiris by the pool is how I recommend everyone spend their summer.

Endnotes: I really admire Michael Adno’s masterful profile of Ernest Matthew Mickler—an artist, a folklorist, a musician, a gay man. If you haven’t clicked on it yet, I’ll link the piece again here. Mickler’s voice weaves throughout the story in such a beautiful way that it makes me emotional. On the idea for the cookbook: “‘We got stoned out of our minds one night, and honey, we were seeing monkeys on the wall almost.’” Adno writes about the reclamation of white trash cooking in such an elegant way, and about Mickler with such care, that it is one of my favorite pieces of writing ever.

The book is one my prized possessions too. I've often thought of doing a follow up; White Trash Gardening. Thanks for link too -- I didn't know anything about him.